BLOG FOSTREN – ISRAEL

Written by Ronen Shmilovitz, Alexander Shestiperov

– What is your country’s stand on coercion reduction?

The Ministry of Health mental health department in Israel declared: “The Mental Health Services in the Ministry of Health are working to protect the dignity of all service users as defined in the Basic Law of Human Dignity and Freedom of 1992 and the Patients’ Rights Law of 1996”.

In Israel, The Mental Patients Treatment Act of 1955 includes a variety of directives involving psychiatric hospitalisation and treatment. The law specifies arrangements for voluntary hospitalisation and treatment as well as involuntary hospitalisation through a civil procedure by the district psychiatrist or criminal procedure by court order. These legal arrangements are supplemented by further operational directives in the Regulations for Care of Mental Patients 1991 and additional local and national directives of the Ministry of Health and Mental Health Division.

The updated data indicates 8,073 involuntary psychiatric hospital admissions in 2021, 34% of all psychiatric hospital admissions. Among those, a three quarter (27%) were by district psychiatrist order, 6% by the court order according to the Mental Health Act, and 0.6% by court order according to the Youth Law At the end of 2021. 83% of persons hospitalised involuntarily, and 56% of those hospitalised voluntarily were males. The percentage of males with involuntary hospitalisations was higher at all ages. During 2021, within involuntary admission, 24% were hospitalised for the first time, and 76% were readmissions. Acute psychotic disorder and drug/alcohol abuse diagnosis were the most frequent admission in 2021.

The guideline in Israel is that a safe clinical environment is a required precondition for the healthcare workforce to provide effective and safe care to their clients. The coercion measures used in mental health services in Israel are seclusion, restraint and involuntary medication administration. Seclusion refers to the confinement of an individual in a padded room or area from which they cannot exit. Restraint refers to using physical restraints, such as handcuffs or straps, in a space that meets all the regulatory requirements to prevent an individual from moving.

Physical restraint should be the “last resort” method for managing threatening situations. Psychiatry coercion measures are well-established and still used only as a safety management strategy in clinical psychiatry. In Israel, a new Mental Health Ordinance from 2018 regulates coercion within mental health services. The ordinance allows coercion measures for individuals’ involuntary commitment Only to prevent physical and immediate danger to the patient or others. There is also a transparent and regulated process for conducting coercive measures.

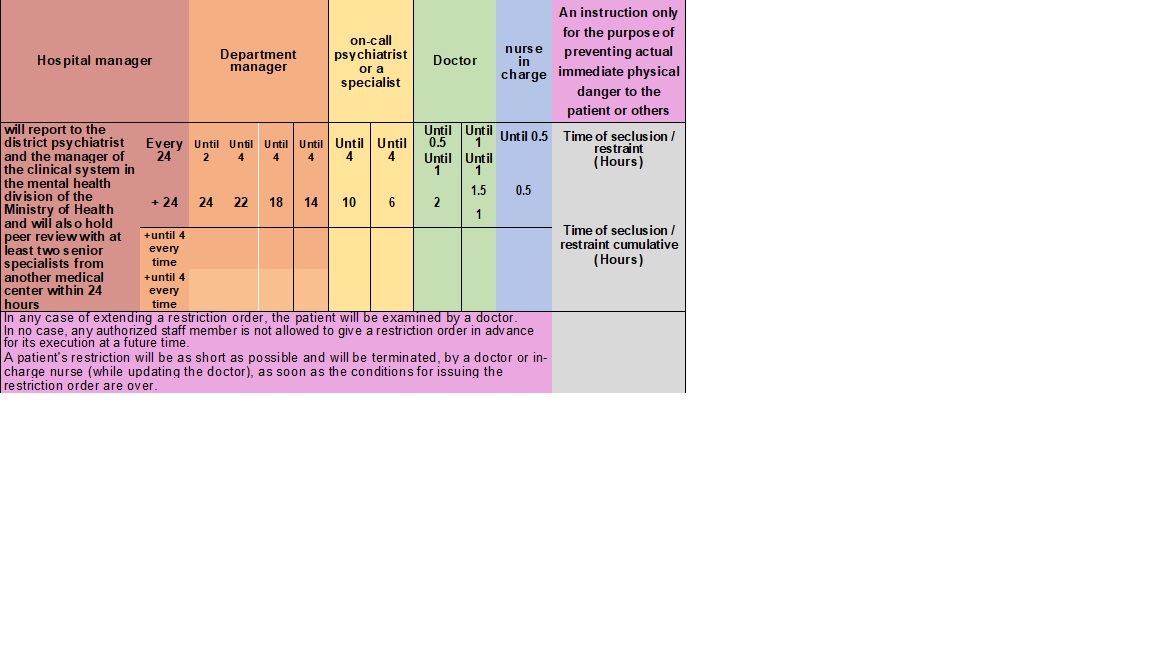

(Fig. 1) Based on a medical examination, A doctor may give a restriction order for a period not to exceed one hour, and he may extend this order for one additional hour (a total of two hours at most from the beginning of the restriction). In the absence of the possibility of waiting until the arrival of a doctor to issue a restriction order, an in-charge nurse may order the mechanical restriction of a patient or his isolation for a maximum period of 30 minutes and immediately call the doctor to come to the ward. In this case, a doctor is obliged to arrive urgently. The doctor will examine the need to extend the restriction and its approval. If a doctor believes that it is necessary to extend a restriction order beyond the period of two hours, he will refer to an on-call psychiatrist or a specialist who is not on-call so that he may assess the need for the continuation of the restriction. The on-call psychiatrist or the specialist may approve the continuation of the restriction up to a period that does not exceed 4 hours and may extend the restriction for four additional hours. At most, 10 hours total from the beginning of the restriction. If the on-call psychiatrist or a specialist who is not on-call believes that it is necessary to extend the restriction order beyond a period of 10 hours, he will contact the psychiatrist department manager so that he can assess the need for the continuation of the restriction. A psychiatrist department manager may approve further extensions of the restriction order for periods not to exceed 4 hours at a time and up to 24 hours from the beginning of the restriction. If a psychiatrist department manager believes that the restriction order should be extended beyond 24 hours, he will contact the hospital manager so that he can assess the need for the continuation of the restriction and approve it. If a hospital manager has approved the continuation of restriction beyond a period of 24 hours, the psychiatrist department manager, psychiatrist on-call, or a specialist psychiatrist who is not on-call will be entitled to approve the extension of the restriction order for additional periods that do not exceed 4 hours at a time, provided that every 24 hours the continuation of the restriction is approved by a hospital manager. If the hospital manager has authorised the extension of the restriction above order, he will report this to the district psychiatrist and the clinical system manager in the mental health division of the Ministry of Health and will work to hold clinical peer review with at least two senior experts from another medical center within 24 hours, as long as the restriction lasts. As part of the clinical peer review, the circumstances of the restriction and the clinical considerations for the restriction will be examined, and an emphasis will be placed on examining alternatives while documenting what is said in the patient’s medical record.

(Fig. 1) Restraint and Seclusion process

Involuntary medication administration is another form of coercion used in mental health services in Israel. The Mental Health Ordinance allows involuntary medication administration to involuntarily committed individuals.

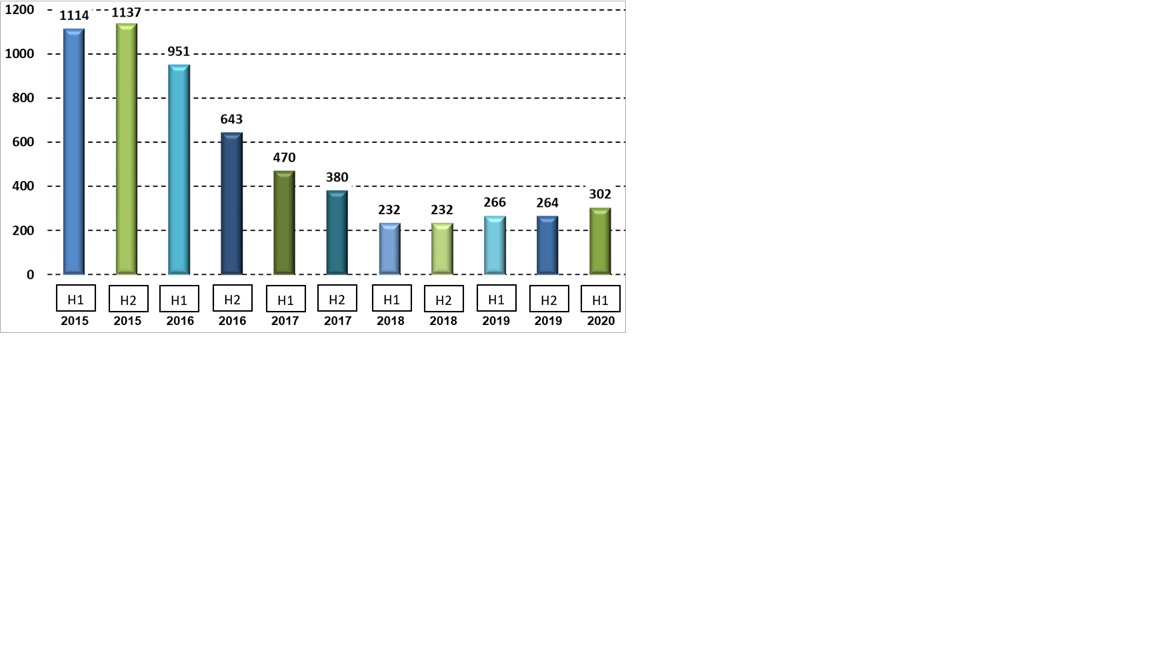

In 2016, patients’ restrictions and isolation caused widespread media coverage. It cast a negative light on the psychiatric hospitalisation system and forced the relevant authorities to make a change. The change began in the staff members’ awareness and perception, learning different treatment methods and concepts, and changing conditions and infrastructure in the wards. Along with the need for change, a committee was appointed by the Ministry of Health CEO to reduce mechanical restrictions in Israel. Among its conclusions was that it is necessary to strive for the number of restrictions to be reduced by 60% yearly. The monitoring of the progressive efforts to reduce restrictions in the psychiatric hospitals began that same year, and the hospitals were requested to transfer to the Department of Mental Health reports on the number of instructions on physical restriction issued by the various departments (Fig. 2).

(Fig. 2) The monthly average of mechanical restraint instructions in the acute wards from 2015 to the first half of 2020

– What kind of research is happening in your country on this topic?

Israel, like many other countries, has been addressing the issue of reducing coercion in mental health treatment through various means, including policy changes, professional training, and public awareness campaigns. The research in Israel deals mainly with violence towards medical staff and not with ways to reduce coercion. The focus is generally on promoting a more patient-centered and rights-based approach to mental health care.

The Ministry of Health and the Mental Health Division dealt with the issue of coercion reduction since 2017. They posted guidelines and recommendations for decision-making to reduce and minimize restrictive interventions in the field of mental health.

– Why are we in the network? What would we like to achieve with it?

As members of FOSTREN, we can achieve the following:

- Networking and Collaboration: FOSTREN brings together professionals, researchers, policymakers, and advocates from various European countries who share a common interest in reducing coercion in mental health care. Being members allows us to network and collaborate with like-minded individuals and organizations, fostering the exchange of knowledge, experiences, and best practices.

- Access to Research and Resources: FOSTREN conducts research and collects valuable data related to reducing coercion in mental health services. As members, we gain access to these research findings, reports, and resources, which can inform and improve our own mental health practices.

- Professional Development: FOSTREN organizes workshops, conferences, and training sessions on topics related to coercion reduction and patient-centered care. These events provide opportunities for professional development, enhancing our skills and knowledge in the field.

- Influence Policy and Practice: Through FOSTREN, members can collectively advocate for policy changes and advancements in mental health services. By participating in the project, we have a platform to influence practices and policies at the regional, national level.

- Implementing Best Practices: FOSTREN emphasizes the importance of evidence-based approaches to reduce coercion. As members, we can learn about and implement best practices that have been proven effective in reducing coercion and promoting recovery-oriented care.

- Raising Awareness: FOSTREN seeks to raise awareness about coercion in mental health services and its impact on patient’s rights and dignity. As members, we can contribute to raising public awareness and reducing the stigma surrounding mental health issues.

- Contributing to Research: Being members of FOSTREN allows us to contribute our research findings and insights to the collective effort of improving mental health care practices.